A Law Director Ignorant of the Law

What does a city do when it realizes that the law director is fueled by rage and retaliation and ignores the law?

PREPOSTEROUS AND ABSURD

Jon Morrow

12/4/202511 min read

Sheffield Lake Law Director

David Graves

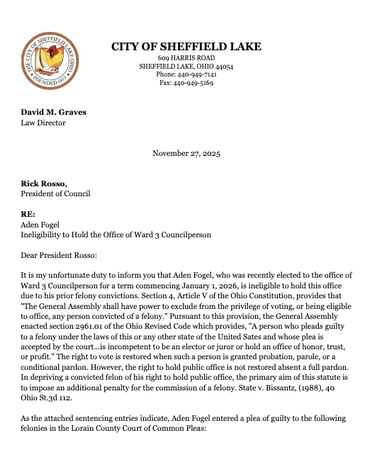

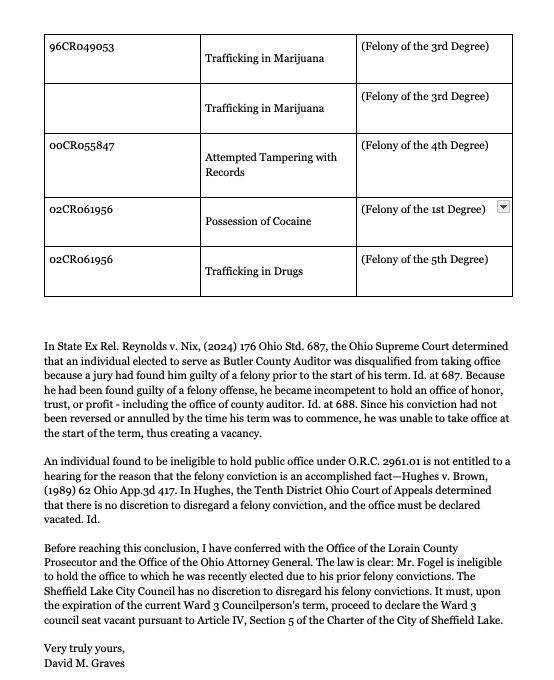

A letter from Law Director David Graves to Rick Rosso ( Sheffield Lake City Council President) - reproduced from a photo as best as possible

Clearly, David Graves has an Axe to grind with Councilman Aden Fogel who overwhelmingly won his Ward 3 City Council Seat....

Law Director Graves has taken the outlandish and foolish approach to attempt to disenfranchise the residents of Ward 3 in Sheffield Lake by suggesting that Sheffield Lake's City Council summarily remove a wildly popular candidate, without a hearing, no less. He bases the grounds for removal on Ohio Revised Code 2961.01 - that a person who pleads guilty to a felony is incapable of holding office in the state of Ohio.

Anyone using Chat GPT, Grok, CoPilot, or Google's AI could easily come to that same conclusion. But the true answer comes in knowing how to ask the proper question and to take in account all the relevant facts. So let's take a deeper look!

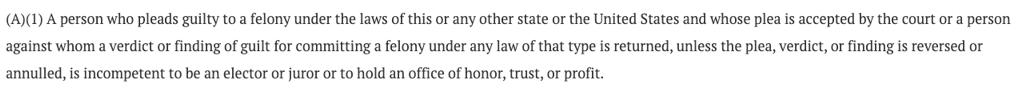

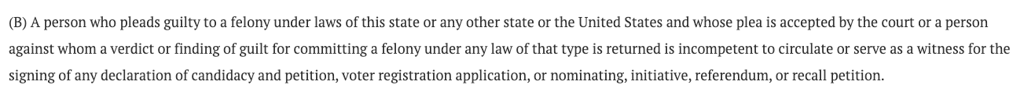

While it is not obvious to the layman 2961.01 (A)(1) spells out that a convicted felon cannot "hold an office of honor, trust, or profit." In legalese speak that means that a felon cannot hold elected office in Ohio. It is unambiguous. Additionally, paragraph (B) of the same section spells out that such a person cannot even circulate their own petition for candidacy.

Clearly and unambiguously, a "felon" cannot hold office in Ohio - so in this respect, the law director is correct, and there is no disagreement here. But we must look at all sections of the law dealing with felons being disqualified from holding office. Including 2967.16 which states:

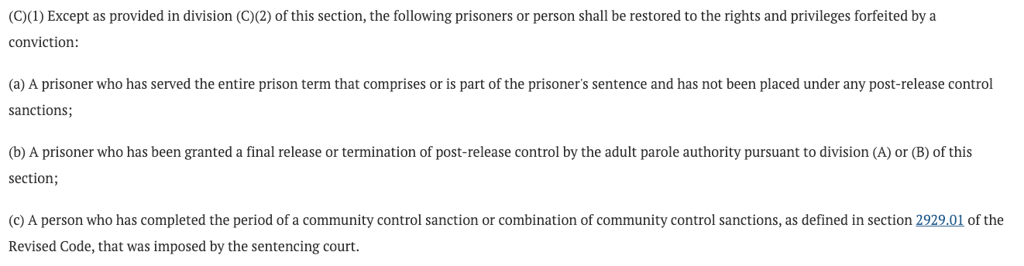

Clearly, this states that a person shall have their rights and privileges "restored" if (a) A prisoner who has served the entire prison term that comprises or is part of the prisoner's sentence and has not been placed under any post-release control sanctions; This means that if you committed a State felony in Ohio your rights are restored when you complete your sentence, probation, and make restitution and you are allowed to run for office.

If it is a federal felony, you would have to get a pardon, or a reversal and annulment of the charge, or have your record expunged or sealed to run for office.

Councilman Fogel was not convicted of any federal felonies and did not serve time in a federal penitentiary. As far as the State of Ohio is concerned, his past crimes have been discharged, and he is fully reformed and able to lead a normal life.

So then, a skeptic of the author will ask, well, that is the author's opinion, and that Graves is a lawyer, and the author is not a trained lawyer, so it stands to reason that the lawyer knows more than the author. While the author is indeed not a lawyer, it does not mean that the author is ignorant of the law, nor does it mean that the law director's opinion of the law is above reproach. The law director claims in his letter that he conferred with the Lorain County Prosecutor and the Ohio Attorney General's Office and that they agree that Councilman Elect Fogel cannot be seated on City Council. So now it is Law Director Graves, Lorain County Prosecutor Cillo, and the Ohio Attorney General's Office that say author Jon Morrow is wrong in his assertions.

I mean proof positive - Jon Morrow does not know the law, he is not a lawyer, and he should just shut up, he is speaking on a subject he does not know. Correct? Wouldn't you trust the people who have the credentials? Don't trust the person with no training....correct? He's just one person with no training - he doesn't know the law at all.

Except that, as a political consultant, I have experience with desperate opponents trying to keep candidates who have won fair and square from taking office through political and legal shenanigans. Often, these shenanigans are so serious that not only do they backfire, but they can also cost attorneys their good standing with the State Bar and the Supreme Court of Ohio through their participation in a pattern of behavior intended to disenfranchise voters by violating professional codes of conduct.

You see, I am very confident that Councilman-elect Fogel can serve because it is not just my opinion - it is also the verified opinion of the Ohio Attorney General which has the full effect of law and how to properly interpret the law.

Ohio Attorney General opinion 2006-030 states - "In sum, it is my opinion, and you are hereby advised that, pursuant to R.C. 2967.16(C), a person convicted of a felony under the laws of Ohio is restored the privilege of holding an office of honor, trust, or profit, which had been forfeited by operation of R.C. 2961.01, when the person is granted a final release by the Adult Parole Authority under R.C. 2967.16(B). Upon the grant of a final release by the Adult Parole Authority under R.C. 2967. l 6(B), such person may serve as a member of a village board of zoning appeals."

Ohio Attorney General Opinion 2008-11 states - "We conclude, therefore, that, in addition to R.e. 2961.01, R.e. 2967.16 ( C) provides the means by which a person may have the privilege of holding an office of honor, trust, or profit restored to him. See State ex reI. Gains v. Rossi, 86 Ohio St. 3d at 622, 716 N.E.2d 204 ("R.e. 2961.01 does not expressly provide that the reversal, annulment, or pardon mentioned in that statute are the sole methods for a convicted felon to restore that person's competency to hold an office of honor, trust, or profit"). See generally Meeks v. Papadopulos, 62 Ohio St. 2d 187, 191-92,404 N.E.2d 159 (1980) ("the General Assembly, in enacting a statute, is assumed to have been aware of other statutory provisions concerning the subject matter of the enactment even if they are found in separate sections of the Code"); Eggleston v. Harrison, 61 Ohio St. 397,404,55 N.E. 993 (1900) ("[t]he presumption is that laws are passed with deliberation and with knowledge of all existing ones on the subject' '). A person convicted of a felony under the laws of Ohio who satisfies the conditions set forth in RC. 2967.16(C) restores the privilege of holding an office of honor, trust, or profit."

Ohio Attorney General Opinion 2009-11 states - "In conclusion, it is my opinion, and you are hereby advised that a person who has been convicted of felony domestic violence under the laws of Ohio and who has not been granted a full pardon by the Governor or had his conviction reversed or annulled or the record of his conviction sealed is barred by R.C. 2961.01 from holding the office of township trustee unless he has had the privilege of holding an office of honor, trust, or profit restored to him, as provided in R.C. 2967.16(C)(1) or its predecessors."

So, this is not the Author's opinion; it is the Ohio Attorney General's opinion. Official AG opinions have the force and effect of law and guide how law is to be interpreted. Ohio AG opinions can be reversed and overruled by court rulings (case law)

According to Graves, however, he uses three cases to support his interpretation of the law as valid for prohibiting Councilman-elect Fogel from being seated.

State v. Bissantz (1988) — a special permanent-bar bribery case, not a general “felon can’t serve” rule

What Bissantz held:

Bissantz was convicted of bribery in office under ORC 2921.02(B). The Ohio Supreme Court said: even if that conviction is later expunged, 2921.02(F) imposes a forever disqualification from public office for that specific crime.

Why it’s misapplied to Councilman Fogel:

Bissantz is about a narrow class of felonies where the General Assembly permanently strips office-holding rights, even after rehabilitation steps like expungement.

The Court itself later distinguished Bissantz by saying that 2961.01 is general and not permanently disqualifying unless a separate statute says so. That distinction is spelled out in State ex rel. Gains v. Rossi (1999).

In other words: Bissantz only bites if Aden has one of the “forever-barred” felonies (bribery in office, theft in office, etc.). If he doesn’t, then Bissantz is irrelevant.

Bottom line:

Using Bissantz as a blanket rule is like citing a treason case to argue that a speeding ticket ends your voting rights. Wrong tool for the job.

Reynolds v. Nix (2024) — about current guilty verdicts causing immediate vacancy, not old felonies after final discharge

What Reynolds held:

A sitting elected official became incompetent to hold office immediately upon a new guilty verdict under 2961.01(A)(1). The Court explained the statute is designed to protect the public during the pendency of appeals, and the vacancy/appointment process can proceed even if the verdict is later reversed.

Why it’s misapplied to Councilman Fogel:

Reynolds concerns a fresh felony guilty verdict while the person is in or about to enter office.

Aden’s situation (as you’ve stated repeatedly) is the opposite:

old felony convictions,

sentence completed,

final discharge obtained, and

no new verdict exists today.

Reynolds says nothing about stripping civil rights after final discharge. It addresses a temporary disability triggered by a currently valid guilty verdict.

Also, note the structure of 2961.01: it creates incompetency upon guilt unless reversed or annulled; but other statutes (and final discharge under 2967.16) restore rights afterward unless a permanent-bar felony is involved.

Bottom line:

Reynolds is about removal during an active conviction. It is not a precedent for blocking a candidate years later who has completed sentence and regained civil rights.

Hughes v. Brown (10th Dist. 1989) — again, about immediate vacancy upon a current felony conviction

What Hughes held (as quoted in Reynolds filings):

Once a felony conviction exists, officials (there, the Secretary of State) have no discretion — the office is treated as vacated under 2961.01 and no additional hearing is required.

Why it’s misapplied to Councilman Fogel:

Same reason as Reynolds:

Hughes presumes a current felony conviction producing present incompetency.

It does not address what happens after final discharge.

It also does not address restoration provisions in 2967.16 (certificate of final release), which explicitly restore forfeited rights unless a permanent-bar statute applies.

Bottom line:

Hughes tells an official what to do when the conviction is live. It doesn’t say the disability is eternal.

Why the Graves letter is just a very poor legal opinion

The letter is leaning on cases without first showing that Councilman Fogel has a permanent-bar felony, it’s skipping the decisive step. Courts hate that kind of shortcut, because it is an attempt to rewrite statutes into something harsher than what the legislature enacted.

Reynolds and Hughes are timing cases (what happens during conviction).

Bissantz is a category case (what happens for certain crimes only).

None of them, on their own, say: “anyone who ever had a felony is forever ineligible.”

Ohio law simply doesn’t read that way.

What Council is facing is not merely a technical disagreement over statutory interpretation. The Law Director’s letter regarding Councilman-elect Aden Fogel, and the selective, strained use of case law to justify disqualification, arrive in a context that cannot be ignored. When legal power is exercised against a political opponent, the law demands not only correctness but the appearance of neutrality. Here, that neutrality is in serious doubt.

The timing and target create an appearance of retaliation

Councilman-elect Fogel has taken public positions that directly oppose policies the Mayor and Law Director have supported — including resistance to new tax levies and criticism of certain zoning changes. He has also been openly critical of the administration’s handling of the unresolved issue involving missing funds from an overpayment to a suspended city employee.

When a legal officer uses his authority to block the seating of the very candidate who has been challenging his policy preferences and integrity, it creates a reasonable perception that the legal action is not purely legal, but political. Even if the Law Director insists otherwise, the burden is on him to show that his conduct is above reproach and firmly grounded in complete, controlling law. The letter does the opposite.

The case law used reads like a weapon, not a guide

The Law Director relies on cases like Reynolds v. Nix, Hughes v. Brown, and State v. Bissantz to assert that Fogel is automatically incompetent to hold office. But those cases are narrowly about:

current guilty verdicts causing immediate vacancy (Reynolds, Hughes), or

specific permanent-bar felonies like bribery in office (Bissantz).

They do not stand for the broad proposition that any old felony conviction, after final discharge, permanently strips office-holding rights. Omitting or downplaying the restoration framework under Ohio law is not a minor technical slip — it changes the entire legal outcome.

When the Law Director presents only the authorities that skew one way, while failing to grapple with the statutory restoration provisions and Attorney General opinions that cut the other way, it looks less like legal reasoning and more like purposeful and intentional outcome-driven argumentation.

Selective legal aggression is itself an abuse of power

A Law Director is not a political actor. He is the City’s legal conscience. His job is to advise Council and the public with complete candor, not to secure a political victory for one faction by “lawfare.”

If legal authority is deployed only when a dissenter threatens the preferred agenda — and not deployed with equal zeal in other contexts — it becomes a tool of intimidation. That is the classic footprint of abuse of office: using a public position to disadvantage opponents under the color of law.

This conduct risks violating rules of professional responsibility

Attorneys, especially government attorneys, are bound by professional duties that go beyond winning arguments. Among other things, they must:

avoid knowingly advancing misleading interpretations,

avoid omitting the controlling authority in a way that materially distorts advice, and

avoid conflicts where personal or political interests appear to drive official legal counsel.

A government lawyer who uses his office to misstate law in a way that disenfranchises voters and blocks an elected official from seating invites scrutiny under those professional standards. Even if one stops short of declaring a violation, the appearance is deeply troubling and warrants independent review.

The pattern matters

This isn’t occurring in a vacuum. Councilman-elect Fogel and I have previously criticized the Law Director’s conduct and competence. I’ve raised concerns about intimidation tactics, selective enforcement of rules, and an alignment with the Mayor’s political objectives.

When a legal officer repeatedly appears on the side of executive retaliation — whether involving speech disputes, levy advocacy limits, or now office-holding eligibility — a pattern emerges. And patterns are what courts and ethics bodies look for when determining whether something is an isolated mistake or a systemic abuse of authority.

The fair, responsible conclusion for the Council

Council does not need to declare the Law Director guilty of misconduct to act.

Council only needs to acknowledge this much:

Given the Law Director’s politically entangled posture, the contested legal interpretation, and the substantial appearance of retaliation against a political dissenter, Council cannot responsibly rely on his opinion alone to refuse seating of an elected official or to validate the Mayor’s use of legal threats. An independent special counsel is necessary to restore public confidence and to protect the City from civil rights exposure.

That conclusion is sober, legally defensible, and morally unavoidable.

The Sheffield Lake Forum

Paid for by the committee - For a Better Tomorrow - Elect Jon Morrow

Text or call

"We all win when we make our voices heard!"

(419) 602-4425

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Disclaimer

The website www.SheffieldLake.community is both a work of irony and a platform of ideas.

It playfully satirizes the hypersensitivities of those who zealously defend Mayor Rocky Radeff’s policies, while earnestly offering real-world proposals for improving life in Sheffield Lake.

This site serves two purposes:

To highlight, through gentle parody, the contradictions and overreactions that too often dominate local discourse, and

To present serious, forward-looking solutions for residents to evaluate and discuss.

While its tone occasionally employs humor and irony, the underlying intent is civic — to inform, challenge, and inspire thoughtful conversation about the future of our city.

Authorized and maintained by Jon Morrow, Councilman-Elect, Ward 1, City of Sheffield Lake.